Monarchy derives from the Greek root word “mono,” meaning one, and “archon,” meaning ruler. This week 249 years ago, the American colonies declared their independence from the British monarchy. They fought a seven-year revolutionary war to win it, and another three-year war in 1812 to keep it. We all continue to fight for our freedoms today – the “No Kings” protests on the one hand, and the anti-COVID-19 protests on the other, are symptoms of that struggle.

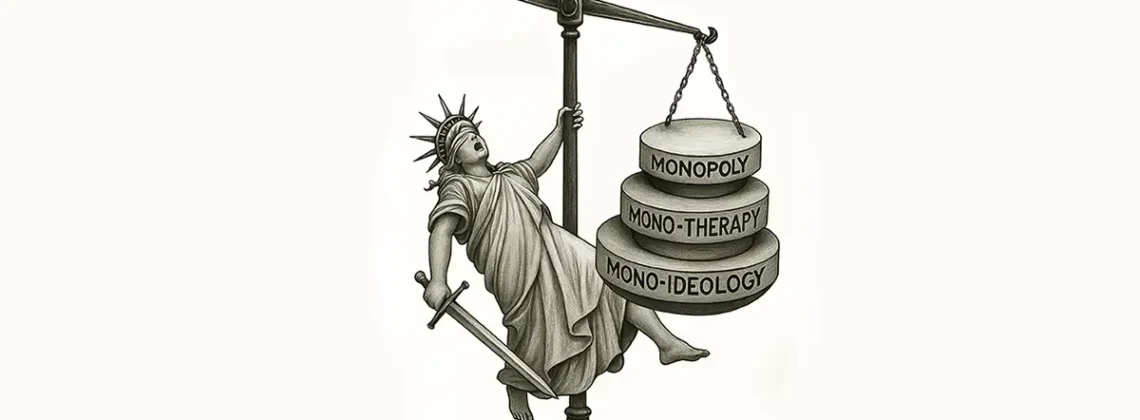

Today, there are at least three central ideas that control our health and health freedom. Each is a single idea that restrains our liberty of conscience, choice, and action.

Each idea is a simplifying assumption that society makes for us, and which prevents us from making our own health choices. None of them is supported by any credible science; in fact, all of the credible science goes against them. Yet these assumptions continue, preventing us from making sensible health choices. These assumptions are:

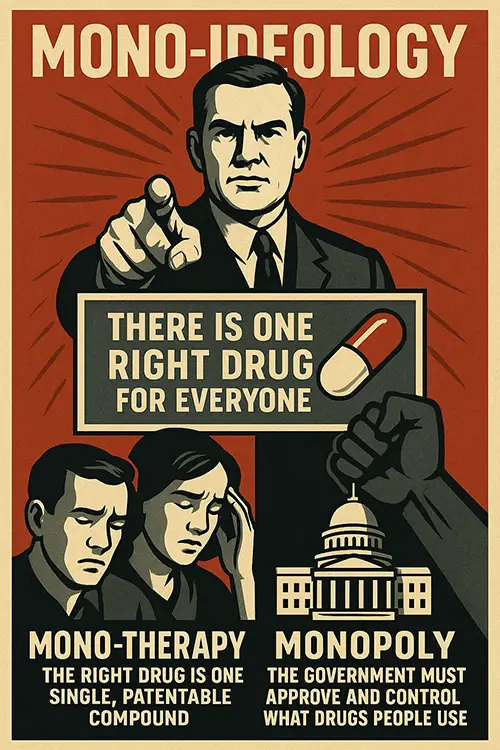

1. Mono-ideology. There is one “right” answer for everyone.

2. Mono-therapy. The right answer is always one single, patentable compound.

3. Monopoly. The government must approve and control what drugs people use.

Mono-ideology

The first of these ideological monarchs is the idea, or rather the logical fallacy, that only one idea can be “right.” While this may be true (to some extent) for scientific laws that govern the universe, it’s usually false where human problems and solutions are concerned. Different people have different needs, so no one rule or solution can possibly hope to serve them all.

Laws of nature are often thought of as universal, but even those are modified by other laws of nature. Matter is solid, until you look at it under an electron microscope. Gravity can bend both space and time. Electrons, protons, and neutrons act like particles in some ways and waves in others. Particles can be entangled at the quantum level in ways that defy easy explanation. The universe isn’t simple, and simple rules are rarely universal. Life is just as complex and interconnected as physics, or more so – flowers depend upon bees, and bees upon flowers, and birds on both. Every form of life fills a niche, and as much as we hate mosquitoes, if we wipe them out, the unintended effects will ripple up the food chain.

We Americans are so entrenched in the competitive idea of winning and losing, that we tend to view any competing or different idea as a threat to our own. We assume that the marketplace of ideas means that one idea must win in the end. But nobody “wins” in a bazaar – they either find what they need, or they go home. There’s no winner, but worse ideas are constantly displaced, and better ideas remain. Even unpopular ideas often find some followers. That’s how liberty and individual choice work.

In medicine, we often assume that there is one right answer for every problem, often described as the “standard of care.” This wrongly assumes that people are all the same, and that this “standard of care” will benefit everyone, from ballet dancers to sumo wrestlers, in the same way. This thinking has created standards of medical education and practice that are enforced by law on everyone, and an official scientific establishment whose assumptions, true or false, must not be questioned. Dissent must be rejected, suppressed as misinformation, or even prosecuted. In religion, this is known as orthodoxy, or in its more extreme forms, dogmatism, fanaticism, zealotry, or bigotry. In any field of human inquiry, the underlying concept is the same: the acceptance of one thought or idea, and the intentional exclusion of all others as a matter of policy or principle.

There is a story that Albert Einstein was asked by an aide if he had prepared the final exam for a physics course he was teaching. Einstein responded that he would use last year’s exam. When the aide objected that those test questions were already known to the students, Einstein assured him it was fine – because all of the answers had changed. This is why “scientific consensus” doesn’t mean much: science isn’t a democracy, and scientists changing the consensus are the only ones who really matter. If we base public policy on scientific consensus, we’ll always be 50 years behind the curve. If we make scientific consensus the law, that consensus will never change – even when it’s clearly wrong.

Mono-therapy

The next ideological monarch is the idea that there is one “best” medicine for every condition or disease. This isn’t just the single “standard of care” idea discussed above – but the additional notion that our one-and-only solution must also be a single chemical compound. Western medicine decided about 1907 that mono-therapy (one treatment) is the only “scientific” approach. This is often described in medical literature as the “magic bullet” or “one disease, one target, one drug” model. This idea grows out of another simplifying assumption: that in a scientific experiment, we must control every variable except the one being studied or tested. Since every human being is different, this isn’t possible, but we generally assume and pretend that it is.

Nature doesn’t use single compounds much. Plants are complex chemical factories that contain a broad variety of chemical compounds that serve a wide variety of needs in the plant. Humans (like other animals) rarely subsist on a single food source and use a wide and varied diet: there is no one “best” food for everyone, or even for any one individual. Individuals need varied diets, and populations even more so. We may talk about “superfoods,” but no one eats only quinoa, alfalfa sprouts, or goji berries.

When one single compound is used to treat a disease, there is generally only one way to increase efficacy: increase the dosage. Statistics tell us that both efficacy and tolerance will vary with individuals. Most individuals will be near the mean (average) value for the group, but some individuals will be more sensitive or resistant than most – and a few will be much more. The dose that causes the desired drug effect (the “effective dose”) in 50% of the population is called the ED50 and is an important safety measure. But since drug manufacturers don’t want their drugs to only work for half the population, the only way to increase efficacy is to use doses well above the ED50 – often 30-50x higher. This treats more patients and sells more drugs, but causes safety, ethical, environmental, and other concerns. Safe and effective are a trade-off, based on dosage – bigger doses are more effective but less safe.

Both Traditional Chinese Medicine and Ayurvedic (Indian) Medicine discarded monotherapy centuries ago. In those traditions, a single herbal drug is only used if an herbal formula isn’t available. Formulas do more with less medicine, and they work more consistently over the broad range of individuals. If you’re sensitive or resistant to one ingredient, you probably respond more normally to others. Many traditional formulas have been used safely and effectively for centuries.

After 100-plus years, Western medicine is just beginning to embrace multi-therapy. The AIDS cocktail was perhaps the first common example, followed by chemotherapy and other compounds that were just too toxic to be used alone. Today, blood-pressure medications are often prescribed in combinations of smaller doses, producing better results with fewer side effects.

However, our entire drug approval system is built around the assumptions that: (1) drugs are single, patentable, proprietary compounds; (2) they must be approved as both safe and effective for a specific disease or condition; (3) only approved drugs can be used at all; but ironically (4) approved drugs can be prescribed for any condition (off-label use). The net effect is that only patented drugs have a pathway to FDA approval, but approval costs (and monopoly markets, described below) drive drug costs through the roof. Worse yet, unexpected side effects of medications are now the No. 3 killer in modern nations, after only heart disease and cancer.

Monopoly

The third ideological monarch is certainly the most painful. In Adam Smith’s 1776 best-seller The Wealth of Nations, he describes the economic system that Britain used in his day. One of his best innovations was his description of the “invisible hand” that sets market prices by supply and demand. In a free economy, where buyers and sellers both have other options, they will agree to a price that makes both parties better off – or if not, they will walk away to pursue other choices. In such an economy, every transaction is what we would call “win-win” in today’s language. But many things can prevent the parties from having other choices, such as when there is only one seller (monopoly), or where the buyer has no time or ability to “shop around” for other choices. Both are very common in medicine and health care. While restaurants advertise menus and prices on the internet and even display menus in display boxes on the sidewalk, hospitals and insurance companies do everything they can to ensure that their customers have little say over prices and premiums, and even less chance to shop around.

Every government is by its very nature a monopoly – elections have consequences. This is just one of the many reasons why the U.S. Constitution called for a Federal government that was very limited in scope. It had the power to declare and wage war on behalf of the States, and to regulate commerce between the States, but most issues were reserved by the 10th Amendment to the various States, or more importantly, to the people. All that changed with the New Deal in the 1930s – the Federal government took on a much larger role. But was that a good idea?

Much of Adam Smith’s economic masterpiece The Wealth of Nations was devoted to cataloging the ills of what he called the “wretched spirit of monopoly.” Smith knew the subject well – for many years in Britain the guilds had maintained monopoly power over their various trades, and the British East India Company, founded by Parliament in 1600, had been abusing both the British colonies and population alike for over 175 years by the time Smith published in 1776. He described the role of competition in securing low prices, good service, innovation, and other benefits; and the laziness, greed, and entitlement that occurred where competition was lacking. He pointed out that natural monopolies (think OPEC in the 1970s) tend not to last very long, but they could be maintained forever by force of law. Nearly a century later, the British East India Company was finally dissolved in 1874.

Colonial monopoly still reverberates today. The 2024 Nobel prize for economics was shared by three U.S. economists who showed that the economic success of former European colonies was largely determined by two factors: (1) the rule of law; and (2) an inclusive (or at least non-exploitive) social order that protected the poor as well as the rich. Where these factors existed, colonies prospered after independence, while colonies that lacked them languished. Even within the United States these factors can be seen – the northern (free) States industrialized and prospered, while the southern (slave) States remained agricultural and poor, eventually deciding the outcome of the U.S. Civil War. Thomas Jefferson himself predicted this outcome in his Notes on Virginia, Query 17 (On Religion). He argued that the religious monopoly and intolerance which then existed in Virginia was already being economically out-competed by both New York and Pennsylvania, which had more democratic and tolerant laws than those of the other colonies. Coming from the then-Governor of Virginia, the most populous and wealthy of the 13 colonies at that time, this is a startling admission.

It’s hard to overstate the economic power of monopolies, or the lengths they will go to destroy potential competitors. Examples include the Carnegie (U.S. Steel) monopoly in the late 1800s, and Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Trust in the early 1900s. Both used every dirty trick at their disposal to put competitors out of business, buying up their bankrupt assets and markets for nearly nothing. Even today, echoes of that robber-baron mentality echo through Silicon Valley and Wall Street, where anticompetitive behavior is considered normal, and venture capitalist Peter Theil famously argues that “competition is for losers.” Monopoly is power, and power is not often willingly surrendered.

What is less apparent and even more sinister is the often too-cozy relationship between Big Business and the government monopoly. If Big Business controls government, it has no need of monopoly – government is the monopoly. Corporate interests can use government regulation and procurement to accomplish all that a monopoly needs. Want to keep competitors out? Just require government approval for any new product, like we have had for drugs since 1938. Want doctors to be able to charge more? Control the educational system that trains and creates them, and the licensing boards that allow them to practice.

Smith’s “invisible hand” of supply and demand doesn’t care what you call a restriction on supply. You can call it reasonable regulation, consumer protection, or fraud prevention. You can call it a license, a registration, or authorization. You can call it a monopoly, a patent, a copyright, or a permit. If it restricts supply, prices go up, and the current suppliers benefit. As Smith explains, instead of the lowest feasible price, buyers are forced to pay the highest tolerable price – and for health care, that is stiff. As the six-fingered man says in the film The Princess Bride, “If you haven’t got your health, you haven’t got anything.” Or to paraphrase Jesus: “What will a man give in exchange for his [health or life]?” (Matt. 16:26, Mark 8:36.)

Doctors and nurses are bound by medical ethics to basic ethical principles: patient autonomy, doing good and not harm, and justice. Health corporations and their executives clearly are not. Medical debt is the No. 1 cause of personal bankruptcy. Americans pay more per capita for health care than any other nation, yet we are among the least healthy nations in the modern World. Medical monopoly is the reason for both the high cost and the poor results.

What’s Next?

Each of these three “monarch” assumptions share a common fate: they will stand there, naked of scientific support, but generally accepted, until we all have the collective courage to say that the Emperor has no clothes. Like Jefferson’s self-evident truths, they only need to be pointed out to be obvious to everyone. Now that we see them, how long will we allow them to control our lives and our health?

Leave a Reply